Tribal Departments & Information

About the Shoshone Tribe

The Reservation

The Eastern Shoshone Tribe has been living in their traditional homelands since time immemorial. Archaeological evidence, including Dinwoody style petroglyphs, artifacts found in Yellowstone National Park and in “high altitude villages” in the Absaroka and Wind River Mountains puts the date at over 12,000 years ago. The Shoshones were the first tribe in the area to have horses, which put them at an advantage over their traditional enemies the Blackfeet.

They battled alongside their allies, the Bannocks and Flatheads, with the Crows and Sioux when they moved into the west. The Ft. Bridger Treaty of 1863 covered most of the tribe’s land from Montana, down through Wyoming to Colorado, west through Utah, and then up through Idaho, totaling 44 M acres. With the coming of the transcontinental railroad the US Government had to make a new treaty with the Shoshone and let Chief Washakie choose a site for the tribe’s permanent reservation – the “Warm Valley” or Wind River Basin, a favorite wintering area, but only covering 4.4 M acres. Subsequent agreements ceded the South Pass and Big Horn Hot Springs regions, and the Dawes allotment gave homesteaders reservation land, leaving only 2.2 M acres. The Shoshone Reservation was established before Wyoming became a state and later renamed the Wind River Indian Reservation after the placement of the Northern Arapaho Tribe in the 1870s

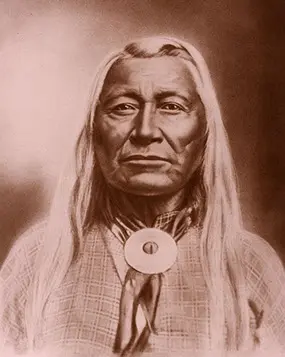

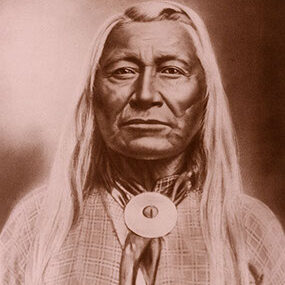

Chief Washakie

Chief Washakie was a highly respected leader, fierce warrior, wise peacemaker, clear visionary, and last chief of the Shoshone Tribe. His bravery shined in battle. He had a rattle he shook to scare his enemies’ horses, which is how he got his name “wase-kie” meaning “rawhide rattle”. Around 1840 he became a principal chief of the Shoshones and later represented his tribe creating treaties with the US Government. With the coming of the emigrant trains along the Oregon Trail, he saw the inevitable expansion of white civilization in the West. He gave protection to those moving west.

When he died in 1900, he was the only Native American to receive full military honors, and the funeral train was 1-1/2 miles long. He is buried in the cemetery that bears his name in Fort Washakie. The army post was renamed Fort Washakie. Chief Washakie led his tribe through a difficult era of change, and was adamant about seeking the good life for his people, realizing the need for education, health care, and the best homeland to secure their future.

Sacajawea

Sacajawea, the famous Shoshone woman who accompanied the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and back, is buried at Fort Washakie in a cemetery that bears her name. Stolen from her Lemhi Shoshone people when she was a young girl, she lived among the Mandans. In her mid-teens, she was married to French fur trader Toussaint Charbonneau, when he was hired as an interpreter for Lewis and Clark. It was a known fact that the Expedition would need to secure horses from the Shoshone people to cross the Continental Divide and that Sacajawea would be valuable in that regard. She also proved her worth in procuring traditional foods and medicines along the trek, all while carrying her newborn baby. She was interpreting for the trade for horses when she recognized her brother, Chief Cameahwait. They had a happy reunion with other family members and with another girl taken captive along with her, but who had managed to escape. Sacajawea saved valuable items when one of the boats capsized and helped guide the corps on the return trip when recognizing certain landmarks in her childhood homeland. Sacajawea rejoined her Shoshone people in later years and has many descendants living on the reservation today.